by Uwe Blesching em 17 de Abril de 2021

Let me start this article by using a few numbers to paint a bit of context: It is estimated that about one third of the entire US population is suffering from chronic pain. That is a staggering number in excess of 100 million people1.

So perhaps it should come as no surprise that US pharmacies fill enough prescriptions to give more than every adult their own daily supply of opioids2!

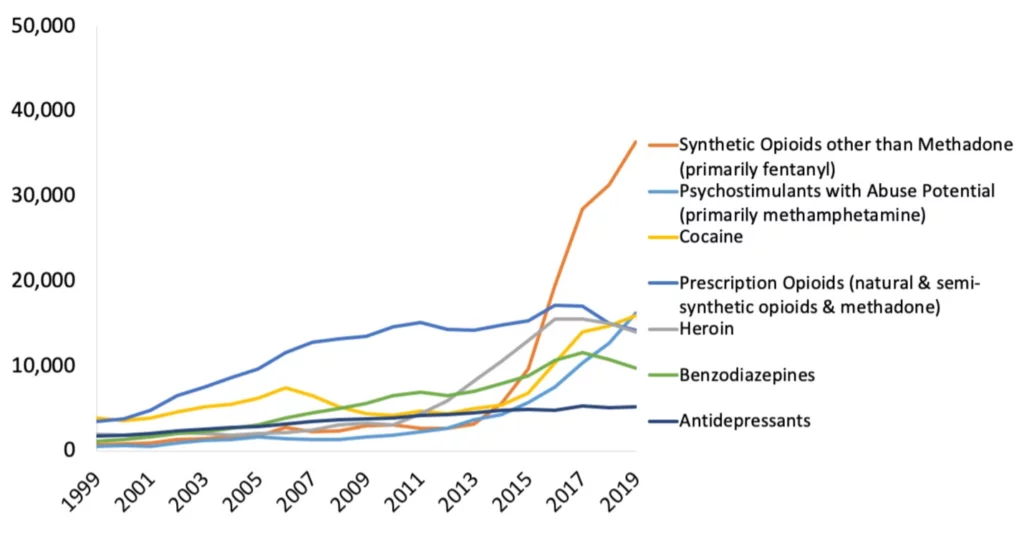

The CDC reports that in 2019 more than 70,000 people died of a drug overdose, and the vast majority of these deaths were due to opioids (see Graphic 1 below).

To provide the reader with some more context: In the entire Vietnam War, 58,220 US soldiers lost their lives. Or here in Berkeley, California, the stadium that is home to the California Bears has a capacity of about 62,000 people.

So many deaths, and in many states these numbers are still rising. However, not in every state: States with legal access to cannabis have seen a drop of up to 25% of drug-related deaths5.

If we were to apply this trend nationally it would mean that roughly 17,500 people may be saved by a single plant.

Cannabis como alternativa para tratar dor crônica

It seems to me that we are a country with a lot of people in pain. And it is a stubborn kind of pain that persists and resists conventional treatment options.

It seems that the current approach relying heavily on opioids has not worked very well. Cannabinoid-based or combination therapies can offer real alternative and not just from a harm-reduction perspective.

The need for alternative pain-relief therapies is enormous, and to date fifteen clinical trials have been published examining the effects of cannabinoid-based therapeutics in the treatment of chronic pain, according to the online platform CannaKeys 360.

Yet US public health officials tasked with the development of policies addressing this very real American tragedy cite the lack of practical, clinical guidance based on the typical gold standard of meta-analyses of double-blind placebo-controlled trials as reason not to move forward with implementing much-needed innovation and change utilizing cannabinoid-based therapeutics.

However, rather than waiting to address this gap between the need and still-developing critical clinical knowledge that is acceptable to the policy-making consensus, in November 2020 a multidisciplinary team from twenty-eight Canadian and US-based academic and research institutions—including experts in the cannabinoid health sciences such as Dustin Sulak, DO, Robert Sealey, MD, Ziva D. Cooper PhD, and Sana-Ara Ahmed, MD (for a complete list see endnotes)—published a solution to this malignant problem in The Journal of Clinical Practice entitled “Consensus‐Based Recommendations for Titrating Cannabinoids and Tapering Opioids for Chronic Pain Control.” In it they report the results of a novel approach utilizing a modified Delphi technique to introduce and titrate cannabinoids while weaning chronic-pain patients from opioid-based analgesics.

Delphi Method: In this context the Delphi process utilized a panel of experts (i.e., Pharmacologists, Toxicologists, Anesthesiologists, Pain Specialists, Experts in the Cannabinoid Health Sciences, Rehabilitation Experts, Addiction Researchers and Treatment Physicians, Neurologists, Oncologists, Psychiatrists, and Psychologists) in an interactive and structured process that systematically evaluated and discerned consensus-based optimal treatment recommendations.

To ultimate arrive at a practical treatment algorithm these experts applied the Delphi method to answers 4 basic and clinically relevant questions:

1. Which chronic pain patients on opioids are possible candidates and which ought to be contraindicated (i.e. should not be given cannabinoid-based therapeutics)?

2. What types of cannabis constituents ought to be used; when should each be given (time of day); at what dosages; and at what dosage progressions?

3. After what point of introducing cannabinoids should the process of weaning opioids begin and what does this process looks like as far as specific dosage reduction is concerned?

4. And, lastly what would be the optimal way to monitor patient progress regarding achieving effective analgesia while reducing any adverse effects potential?

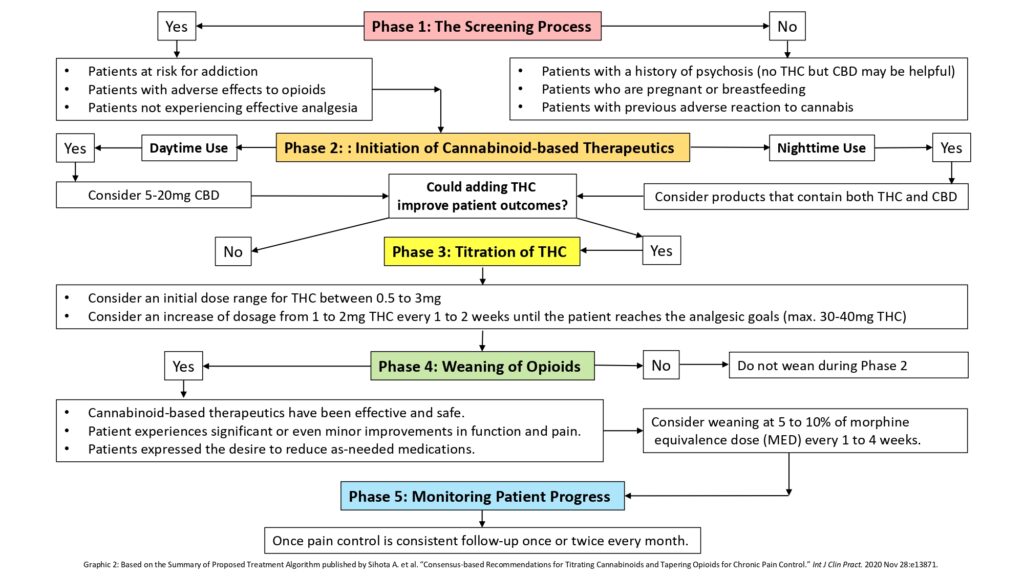

The resulting treatment algorithm was expressed in five distinct phases (for more details on each phase, see the text below Graphic 2).

Phase: The Screening Process (of chronic pain patients on opioids)

Possible criteria for inclusion:

- Patients at risk for addiction

- Patients with adverse reactions to opioids

- Patients not experiencing effective analgesia (despite maximum attempts at adjunctive interventions, i.e., evidence-based psychological, physical therapeutic approaches and/or other pharmaceutical options)

Patient populations considered contraindicated:

- Patients with a history of psychosis (no THC but CBD may be helpful)

- Patients who are pregnant or breastfeeding

- Patients with previous adverse effects from cannabis

Other considerations:

No age restriction was recommended for either THC or CBD, but the use of THC for children was paired with the notion that it should be carefully considered due to the still-growing nervous system (until the age of 25) and THC’s potential impact on it. However, the consensus was that if a pediatric patient was already on opioids, the introduction of cannabinoids ought not to be a contraindication.

Based on clinical observations in other patient populations, a high dose of CBD was considered safe for children.

Phase 2: Initiation of Cannabinoid-based Therapeutics

Preferred method of administration was ingestion and the utilization of oil-based extracts (incl. sublingual tinctures) or capsules, which would ideally be composed of standardized plant constituents. As an exception, in cases of breakthrough pain, vaporized cannabis flower utilizing a medically approved device was recommended.

Daytime Use: Consider 5-20mg CBD a day

Nighttime Use: Consider products that contain both THC and CBD.

Could adding THC improve patient outcomes?

Phase 3: Titration of THC

Consider an initial daily dose range for THC between 0.5 and 3mg.

Consider a daily increase in dosage of 1 to 2mg THC every 1 to 2 weeks until the patient reaches the analgesic goals (max. 30-40mg THC daily).

Also, further cannabinoid titration ought to be stopped if:

- Further increases do not improve their experience of pain

- In the presence of opioid withdrawal symptoms (slow or pause opioid weaning)

- In the presence of cannabis-associated adverse effects

- With the use of other recreational substances

- With the development of psychotic symptoms

Comments:

- In case of adverse effects, a licensed health care professional may opt to reduce the dose.

- Physicians may speed the increase of THC if the patient’s need demands it.

- Be mindful of potential age, sex, and comorbidity-based differences of effects. For example, females may be more sensitive to the effects of THC than males.

Phase 4: Weaning of Opioids

Is weaning of opioids an option?

Possible criteria include:

- Cannabinoid-based therapeutics have been effective and safe

- Patient experiences significant or even minor improvements in function and pain

- Patient expressed the desire to reduce as-needed medications

Consider weaning at 5 to 10% of morphine equivalence dose (MED) every 1 to 4 weeks.

Other considerations:

- It has been recommended not to wean opioids during the initiation phase.

- Furthermore, it has been recommended not to taper opioids based on cannabinoid dosages but based on improvement of pain and function..

- Specific titration ought to be guided by individual patient presentations and in a collaborative decision-making process with the patient.

- Some patients may benefit from a more rapid weaning approach.

Phase 5: Monitoring Patient Progress

Once pain control is consistent, follow up once or twice every month.

If pain control is consistently achieved, follow up every 3 months to track clinical signs of successful treatment defined by the authors of this trial as:

- Improvements in quality of life

- Improvements in specific functions

- Equal or larger than 30% reduction in the intensity of their chronic pain

- Equal or larger than 25% reduction in the patient’s dose of opioids

- Reduction of opioid dose to less than 90mg MED

- Reduction in opioid-associated adverse effects

The authors also make the important point that these consensus-based recommendations ought to take a secondary role after considering each patient’s individual preferences and experiences in addition to each treating physician’s clinical rationale and individual patient assessment.

References

1. Johannes CB, Le TK, Zhou X, Johnston JA, Dworkin RH. “The Prevalence of Chronic Pain in United States Adults: Results of an Internet-Based Survey,” Journal of Pain 11 (2010), 1230–39.

2. Levy B, Paulozzi L, Mack KA, Jones CM. “Trends in Opioid Analgesic-Prescribing Rates by Specialty, U.S., 2007–2012,” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 49:3 (September 2015), 409–13.

3. National Institutes of Health. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Overdose Death Rates. Retrieved March 27, 2021. https://www.drugabuse.gov/drug-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates

4. National Archives. Military Records. Vietnam War U.S. Military Fatal Casualty Statistics. Retrieved March 27, 2021. https://www.archives.gov/research/military/vietnam-war/casualty-statistics

5. Bachhuber MA, Saloner B, Cunningham CO, Barry CL. “Medical Cannabis Laws and Opioid Analgesic Overdose Mortality in the United States, 1999-2010” [published correction appears in JAMA Intern Med. 2014 Nov;174(11):1875]. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(10):1668-1673.

Lopez, Cesar D. BS; Boddapati, Venkat MD; Jobin, Charles M. MD; Hickernell, Thomas R. MD. “State Medical Cannabis Laws Associated with Reduction in Opioid Prescriptions by Orthopaedic Surgeons in Medicare Part D Cohort,” Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons: February 15, 2021-Volume 29-Issue 4-p e188-e197.

6. CannaKeys.com. Chronic Pain. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

7. Sihota A, Smith BK, Ahmed SA, Bell A, Blain A, Clarke H, Cooper ZD, Cyr C, Daeninck P, Deshpande A, Ethans K, Flusk D, Le Foll B, Milloy MJ, Moulin DE, Naidoo V, Ong M, Perez J, Rod K, Sealey R, Sulak D, Walsh Z, O’Connell C. “Consensus-based Recommendations for Titrating Cannabinoids and Tapering Opioids for Chronic Pain Control.” Int J Clin Pract. 2020 Nov 28:e13871.

Lista das instituições acadêmicas que participaram do estudo citado:

- Faculdade de Ciências Farmacêuticas, Universidade de British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canadá.

- Divisão Médica, CTC Communications, Mississauga, ON, Canadá.

- Diretor Médico, Anesthesiology and Interventional Chronic Pain, Ahmed Institute for Pain and Cannabinoid Research, Calgary, AB, Canadá.

- Departamento de Medicina Familiar e Comunitária, Universidade de Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canadá.

- Departamento de Anestesia, Clínica da Dor Michael G DeGroote, Hamilton Health Sciences, Universidade McMaster, Hamilton, ON, Canadá.

- Departamento de Anestesia e Medicina da Dor, Hospital Geral de Toronto, University Health Network, Universidade de Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canadá.

- Departamento de Psiquiatria e Ciências Biomédicas, UCLA Cannabis Research Initiative, Jane and Terry Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior, Universidade da Califórnia, Los Angeles, CA, EUA.

- Departamento de Medicina Familiar, Universidade McGill, Montreal, QC, Canadá.

- Max Rady College of Medicine, Faculdade de Ciências da Saúde de Rady, Universidade de Manitoba, e Cancer Care Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canadá.

- Programa Integral Interdisciplinar da Dor, Divisão de Medicina Física, Instituto de Reabilitação de Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canadá.

- Departamento de Medicina, Secção de Medicina Física e Reabilitação, Universidade de Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canadá.

- Faculdade de Medicina, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St John’s NL, Canadá.

- Translational Addiction Research Laboratory, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Toronto, ON, Canadá.

- Clínica de Investigação e Tratamento do Álcool, Programa de Cuidados Agudos, Centro para a Viciação e Saúde Mental, Toronto, ON, Canadá.

- Campbell Family Mental Health Research Institute, Centro para a Toxicodependência e Saúde Mental, Toronto, ON, Canadá.

- Departamento de Farmacologia e Toxicologia, Universidade de Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canadá.

- Departamento de Psiquiatria, Universidade de Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canadá.

- Instituto de Ciências Médicas, Universidade de Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canadá.

- British Columbia Centre on Substance Use, Vancouver, BC, Canadá.

- Departamento de Medicina, Universidade de British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canadá.

- Departamentos de Ciências Neurológicas Clínicas e Oncologia, Cátedra Earl Russell em Medicina da Dor, Universidade Ocidental, Londres, ON, Canadá.

- Clínico Geral, Lloydminster, AB, Canadá.

- Departamento de Anestesia, Universidade McGill, Montreal, QC, Canadá.

- FCFP Director da Clínica Politécnica de Toronto, Professor da Universidade DFCM de Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canadá.

- Especialista em Medicina Canabinoide, Victoria, BC, Canadá.

- Integr8 Health, Falmouth, ME, EUA.

- Departamento de Psicologia, Universidade de British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canadá.

- Departamento de Medicina Física e Reabilitação, Stan Cassidy Centre for Rehabilitation, Fredericton, NB, Canadá.